"Lucina sine concubitu" and "Concubitus sine Lucina"

$750

[JOHNSON, Abraham, i.e., John Hill.]

Lucina sine concubitu. Lettre addressée à la Societé Royale des Londres, dans laquelle on prouve, par une évidence incontestable, tirée de la raison & de la pratique, qu’une Femme peut concevoir & accoucher, sans avoir de commerce avec aucun homme.

S.l., s.n., 1750 (First French edition). Translated by Jean-Pierre Moët.

Bound with:

[ROE, Richard, i.e., John Hill[?]]. Concubitus sine Lucina, ou Le Plaisir sans Peine, response a la letre intitulée Lucina sine concubitu.

Londres, 1750. Translated by Anne-Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon.

8°: π6 A-C8 D6 (-D6) [$4 (-D3,4) signed]; [2], [i] ii-x, [1] 2-57 [58] pp.; 8°: A-C8 C6 ; [$4 (-A1,2, D4) signed]; [1-5] 6-59 [60] pp. Contemporary calf, raised bands on gilt spine with title label in morocco, blind rules with gilt ornaments on the covers, marbled end papers; head showing the onset of splits, joints a bit worn, outer leaves starting to tan, otherwise a nice copy.

PDF description: Lucina sine concubitu

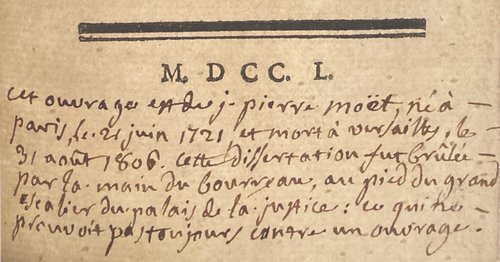

A near contemporary witness: “burned in front of the Palais de la Justice”:

The first title bears a note in an early 19th cen. hand, “Cet ouvrage est de Jean-Pierre Moët, né à Paris, le 21 juin 1721 et mort à Versailles, le 31 août 1806. C’est dissertation fut brûlé par le main de Bourreau au pied du grand escalier dans le palais de la justice, ce qui ne prouvait pas toujours contre un ouvrage [This work is by Jean-Pierre Moët, born in Paris on June 21, 1721 and died in Versailles on August 31, 1806. This dissertation was burned by the hand of the executioner at the foot of the grand staircase before the Palace of Justice, which does not always discredit a work].”

Lucina sine concubitu, written by John Hill (1714-1775) under the pseudonym Abraham Johnson, is a satirical text aimed at mocking the Royal Society of London. Hill had hoped to be elected a member of the society based on his work in botany and medicine, but was rejected, in spite of his scholarship and well-placed supporters. Hill went on to publish many works, notably The Vegetable System (1759-75), a 26 vol. botanical work that followed Linnaeus’s naming system.

Lucina sine concubitu, which claims to prove, “by incontrovertible evidence, drawn from reason and practice, that a woman can conceive and give birth, without having intercourse with any man” played on current interest among scientists in the notion that, “that human seed, or spermatozoa, floated everywhere in the air” (as argued by William Wollaston in Religion of Nature Delineated ). To exploit this, Johnson [i.e., Hill] purports to trap the floating spermatozoa with a machine of his own invention, one that he will make available for examination to the public’s satisfaction, and thus restoring the honor of all women who have conceived without a husband.

Bound with the much scarcer response:

Very soon after the appearance of Lucina, came a follow up signed by Richard Roe [believed written by Hill], Concubitus sine Lucina, ou Le Plaisir sans Peine [Intercourse without Childbirth or, Pleasure without the Pain], which attacked the original, particularly Hill’s science. In this rebuttal to Johnson’s [i.e., Hill’s] initial work, Roe [i.e., also Hill] asks the mocking question, why would woman wish to experience the pain of childbirth without the pleasure of intercourse? By satirizing his own satire, Hill doubles his rhetorical game in a manner that would please Nabokov, pitting his two pseudonyms against each other while also fanning the flames (pun intended) of the original controversy… which, as the manuscript note in our copy suggests, did not discredit the work.

A Translator’s testimony confirming Johnson’s [i.e., Hill’s] theory:

Our edition of Lucina is one of two translations that appeared immediately after the English original, one by Etienne Sainte-Colombe and our copy by Jean-Pierre Moët (1721-1806). Moët’s translation is prefaced by his personal experience with the same phenomenon described in the text, which he relates in the preface: “I had been in London on business for 14 months and 17 days, not once having even gone out strolling in Greenwich or Chelsea, when I learned, from a letter dated March 20 at Bordeaux, that my dear wife had given birth to a healthy boy… a piece of news that struck me like a blow from a knife…” Fortunately, Moët stumbled upon a copy of Lucina in a London coffeehouse, which scientifically demonstrated his wife’s fidelity: it was in fact the southeasterly wind off the coast of Bordeaux, impregnated with molecules organiques from members of the French naval fleet, that led to her condition. Thus, Moët’s translation carries with it an authenticating testimony for Hill’s original, and preserves the honor of his wife!

All of Hill’s cleverness led to the book’s suppression and it appears in Pia’s Les Livres de l’Enfer, p. 442, c.832.