Is a man apparently without testicles capable of carrying out his marriage duties? A 16th century legal opinion.

Two Influential Legal texts of the late 16th century (1595-1600), bound in one volume, including Roulliard's renowned argument addressing whether a man without testicles can consummate his marriage...

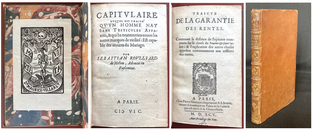

Roulliard, Sébastien. Capitulaire auquel est traité qu’un homme nay sans testicules apparens, & qui ha neantmoins toutes les autres marques de virilité: est capable des oeuvres du mariage

Paris: [s. n.], M VI C. [1600]. First edition.

8°: A-B8 C4 D2 [$4 (-C3, D2) signed]; [2], 1-30 30-40, [1] pp. [=42 pp] (pagination error in which page 30 appears twice; the verso of the final printed leaf is blank). Polished tan calf, 5 raised bands on the gilt spine, title label, boards with blind rules, gilt on the edges of the boards, marbled endpapers. Exlibris of Dr. Maurice Villaret (1877-1946), a well-known neurologist.

Another edition of 1600 (Paris, Chez Claude Morel) has been noted with 62 pp., the text of which is a different setting of the type that conforms to our edition. Leber and Gay trace copies dated 1600, but do not distinguish which edition they report. We trace no copy of our edition in OCLC, CCFr, or in auction sales.

The lawyer Sébastian Rouillard delivered this renowned speech in 1600, in defense of the Baron Charles d’Argenton, whose wife, Madelaine de La Chastre, sought to annul their marriage on the grounds of the Baron’s failure to consummate the marriage, ostensibly due to the lack of testicles.

Madame de La Chastre brought the matter before the courts, and won. The Baron appealed the sentence, maintaining that he had consummated the marriage, and demanded that his wife might be inspected, alternately offering to [demonstrate] congress as his ultimate defense. Rouillard, his counsel, one of the most learned advocates of the parliament of Paris, published this text on the occasion, establishing “that a man born without any visible testicles, but having all the other marks of virility, is capable of the conjugal duties.” This was the Baron’s case, one he offered to demonstrate to the court, if required, thus turing the tables on Madame de La Chastre, who declined either a congress or an inspection, both being equally offensive to her modesty. (cf. London Medical Gazette, Nov. 26, 1836. William Cummin, MD. p. 293.)

Rouillard’s speech, which was admired and employed by other attorneys, is at times technical but very direct and to the point, while also enhanced by the occasional witty, if licentious, Latin and Greek references, without falling into parody or buffoonery. The great popularity of Rouillard’s text is witnessed in its multiple reprintings.

Bayle, Dictionnaire historique et critique, vol. 12, pp. 386-392; Gay, II, p. 114-15 (‘autrefois regardé comme un des chefs-d’oeuvre du genre ’); Hahn, Dumaître and Samion-Contet, Histoire de la médecine et du livre médical, p. 251; Sue, Anecdotes historiques, littéraires et critiques sur la médecine, pp. 121-122.

Bound with:

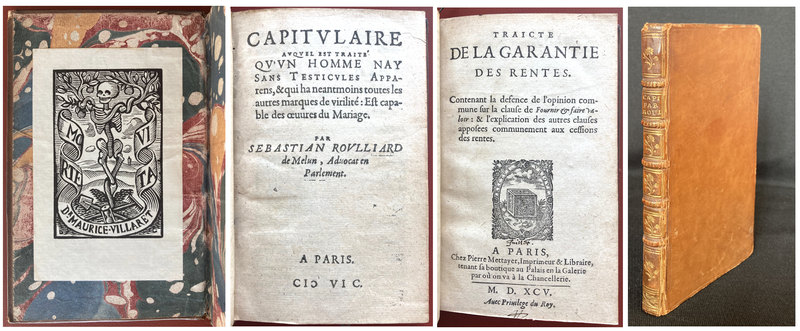

[Charles Loyseau]. Traicté De La Garantie Des Rentes. Contenant la défence de l’opinion commune sur la clause de Fournier & faire valoir & l’explication des autres clauses apposees communement aux cessions des rentes.

A Paris, chez Pierre Mettayer ... 1595

8°: A-P4 [$3 signed]; [1] 2-56 leaves (foliated on the rectos). First edition—rare: only 3 copies located (BnF, Grenoble, Hamburg)

In his Traite de la garantie des Rentes (1595) Loyseau examined the question of creditors’ right to recover debts from the lands of defaulting debtors. Declared by the author to have been prompted by immediate issues- the difficulties that the civil war had brought upon so many French families, and his own rejection of views lately published by Antoine Hotman – Loyseau’s treatise bore upon fundamental problems concerning definition of ownership and distinction between real and personal obligations, questions that challenged French lawyers throughout the century. This copy belonged to a lawyer, as indicated by the former ownership signature on the verso of the title page.

Charles Loyseau (1564-1627) was a grandson of a laboureur of Nogent-le-Roi in the Eure valley, son of an avocat in the Parlement of Paris, godson of the famous Diane de Poitier, and protégé of Catherine de Gonzague, Duche of Longueville, who in 1600 appointed him bailli in the county of Dunois. He eventually joined the bar of avocats at Paris, and in 1620 was elected president of their Order. Early in his career he had published treaties on technical and controversial questions.

Traite de la garantie des Rentes marks Loyseau’s ongoing interrogation of the legal questions related to not only properties rights, but also the social questions raised in the aftermath of civil war, which he further developed in his Traite du deguerpissement et delaissement par hypothèque (1602). He approached the problem by noting how “our customary laws... are so different and so confused that it is very difficult to extract from them a general and certain answer. In order to do so ‘the theory of the law’ must be married with the practice, usage with reason: in short, Roman law must be linked with our own.” (Cf. Howell A. Lloyd. “The Political Thought of Charles Loyseau.” European Studies Review, January 1, 1981, Volume: 11 issue: 1, page(s): 53-82.